Traducción al español por Ana Larrea

Derive happiness in oneself from a good day’s work, from illuminating the fog that surrounds us.

– Henri Matisse

– Henri Matisse

Blanca Guerrero paints as though she is carefully toeing a line between the surface of her canvas and what might exist immediately below. Repeatedly through this new body of work she asks the viewer to change their perspective, proposing that they navigate their way into impossible settings: between the fibers of single-ply paper, or nestled into pockmarks left after several glazes have been sanded away. And then, once there, she insists that you stay.

This second solo exhibition began as a reaction to I Sink into the Blue, her first solo show following a two-month studio residency in the small city of Kōfu, Yamanashi, Japan. Those paintings evoked the deep blue of the landscape, formed into rigid shapes of cisterns, baths, and reflecting pools.

To Sink, Revisited, departs from there. It is instructive to regard what Guerrero has carried over from her previous works—washi-paper collages, light-colored backgrounds, multi-layered washes of pigment—as well as what she has discarded. The new paintings are reflective of different environments: physically surrounded in the industrial landscape of the Gowanus canal, which her studio overlooks; psychically embedded in a social-political moment where past ease and comfort have been shaken, where gray-areas dominate what were previously sharply demarcated boundaries; and all reached in a moment of personal rediscovery.

Gone are the bright, deeply saturated pools of color present in her past works (surely a nerve-wracking decision for a painter aware of their appeal to viewers). Instead, Guerrero has harnessed a new confidence by recasting the focus of the viewer toward more hypnotic gestures. Her palette is much more controlled, narrow. She’s broken away from the perfected geometric-fencing that completely bounded her earlier works, which framed the “subjects” within her pictures. Instead, she requests a trust from her audience, asking that they will look deeply at the paint with fewer signposts pointing to where their eyes should venture. She has crafted entry points to elusive spaces, demanding an audience that is patient and focused.

The resulting body of work draws as much focus to process as it does to end results. This is demonstrated in Niebla, M I (Figure 1). The picture consists of washi paper, painted and squeegeed to plunge pigment into the fibers, only to cover her own mark making by pasting the painted surface of the paper onto the canvas. The result, however, is to highlight the individual fibers of the paper, emerging as branching soft clouds from an inky backdrop.

In this way, echoed by the title of the show, Guerrero relinquishes control. The commandment “sink into the blue” has become simply, “sink.”

***

Many painters speak of seeking a “flow-state” in the studio, of entering into a meditative process where the mind turns off and the decisions seem to be arrived at automatically. But “meditation” can become one of those meaningless catch-all terms that vacillates between the nuances of Agnes Martin’s repetitive mark making to new age self-care apps advertised on subway platforms or as sponsored interstitials inserted into your favorite podcasts.

Guerrero eschews this reductive framing. She recognizes that the desire to be meditative can itself become anxiety producing, and incorporates this tension into her works. Though sinking can be meditative, it can also be hypnotic, indicating a loss of control. It can express a depressive turn, it can capture us at our most alone. Yet sinking can also mean going deep, until you reach a depth at which you become buoyant. You become still, float, in surroundings which mimic your density, your bodily and mental composition. Her new works, breaking out of clearly marked boundaries, provide access to greater depths

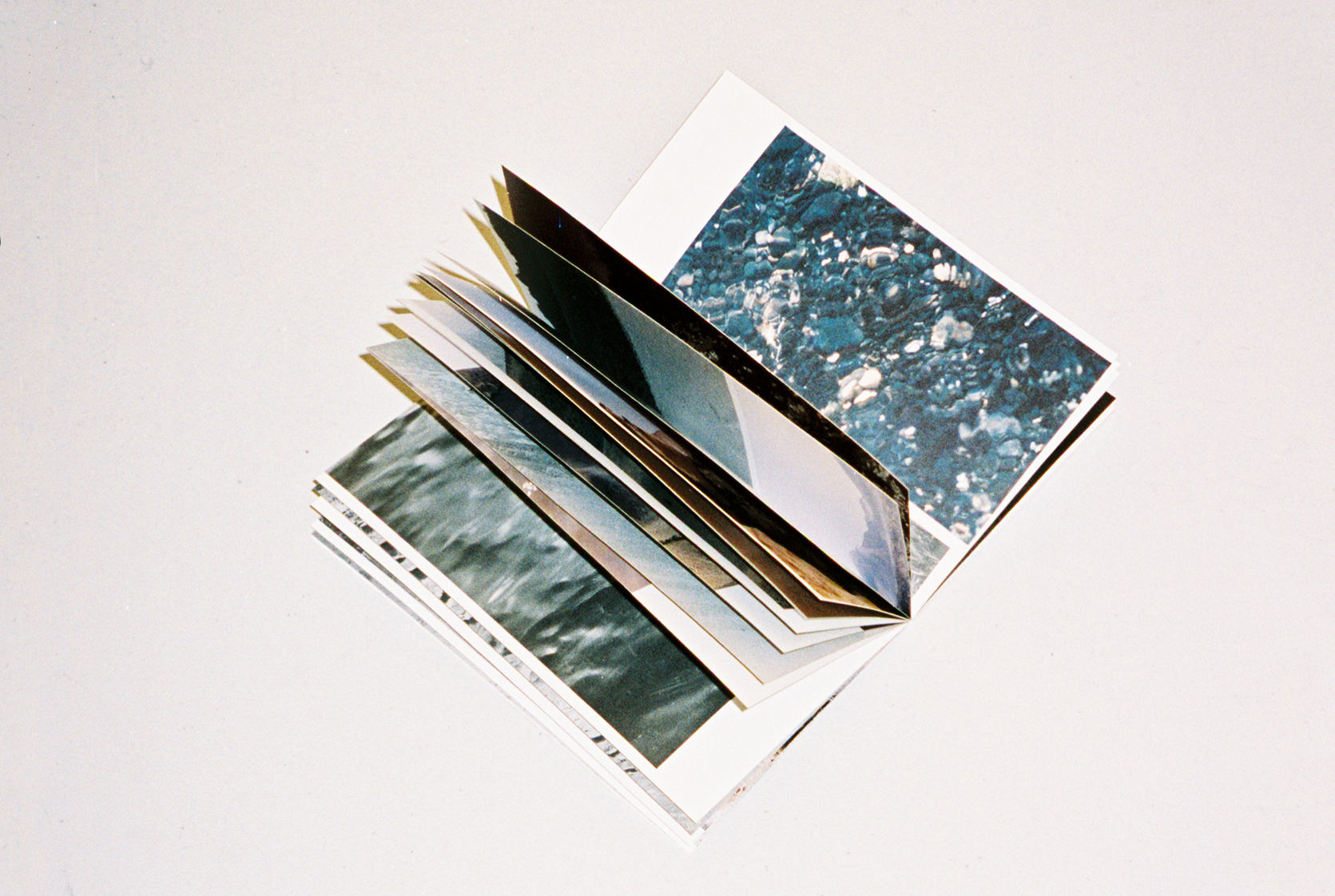

Guerrero’s photographs (collected herein) present her audience with a comprehensive entry-point into her paintings. She understands that film photography is necessarily representational, and uses it to her advantage. Whatever tones, shapes, and textures emerge are gathered from light reflected off a real scene. This is an unspoken agreement with the viewer—I’ll direct your eye, I’ll choose the frame, and you can see the world as I see it.

Photography allows us to stop time. This is one of the benefits of snapshots—friends frozen in a moment over birthday cake, mouths open in laughter. In this way, photography lets us dwell in memory. Guerrero, however, employs photography not to preserve what one would typically remember from a scene, but as a point of redirection—she trains the viewer’s focus on that which is often overlooked. She requests you recalibrate your optic nerve, your subject of attention:

Here is a pile of concrete rubble. The gray is not gray—it is brown, yellow, dusk-colored creamy chalk, white, blue, green, and lavender.

Here is a hasty glob of caulking. The white stalactites are simply impasto-strokes of paint.

Framing is key to Guerrero’s photographs, which are close-cropped so as to demand a bit of extra mental work—removing contextual clues to allow shape and light and texture take precedence over outline and understanding. She indicates her reverence of the natural world, and its human mimics, admiring the details by abstracting their meaning.

Through Guerrero’s lens, construction waste is process painting. Piles of sand are accumulated pastel dust. Dunes and eroded cliffsides become loose flakes of paint. She asks the question: Is it possible, in any image of a landscape that includes sky, or of water, to see anything but an abstraction? Is there any portion of sky or water that isn’t defined by its boundaries?

Flipping the page, one can see the through-line from photos to paintings. Compare Niebla, S I (Figure 2) with this photo of water (Figure 3). Filling the frame, or only giving mere suggestions to an edge allows water to become sand, and then a ridged pattern of purple-velvet burning at the edges. The deeply worn footpaths riding the crest of a brown hill suddenly becomes the slice of a palette knife, blurring the well-defined topography.

The photographs and paintings complement, and draw off one another. Glimpsing them quickly, back and forth, I sense a painter working hard, refining her craft—not only in laying paint and gaining technical proficiency, but the much harder craft of looking, of seeing, and of establishing a viewpoint

The result is a magic trick. Guerrero’s inclusion of photographs could have asked the viewer an obvious question: look at my paintings and see geography. Instead, these paintings demand that the viewer look back at the geography and perceive mark-making. Accidental meeting intentional. The light on a wall plucks shadows from the imperfections in poured concrete slabs which are simultaneously gridded and leveled. Blades of grass are pencil strokes against the duplicate earthen path worn over by car tires. Waves on the sand become a riddle, asking the viewer to guess where the surface of the water resides.

The irony, of course, is that the paintings in To Sink, Revisited are incredibly difficult to photograph, in the way that fog, once illuminated, becomes flat. These are paintings that resolutely do not accommodate being viewed via thumb-scrolling on a small screen. They are almost engineered to confound algorithms, which are optimized to present contrast and clarity, to minimize noise and grain, and reduce images to flat and pleasingly backlit blue-shifted pixels. These algorithms despise subtlety—it is hard to categorize, index, and sell to advertisers (imagine the distraught sales team at Instagram, trying to decipher photo-tags “#bluegray #bluergray #alittlelessbluegray” in service of toothpaste and outerwear recommendations).

Having followed Guerrero’s work from afar for several years, relying on digital photos and images embedded in emails and text-messages, I was struck at the experience of again viewing these same works in person. Even though I’ve observed the way that she paints, when I look at the surfaces of this collection of paintings I imagine them as acts of uncovering, like dragging a wet sponge across the surface of the paint, using slight touch to remove layers of pigment like accumulated dust, brushed away one micrometer at a time. This does not translate to fast, digital viewing, which fails to capture the depths of her delicate touch.

Let me pause for a moment here to address the obvious. Guerrero is a small woman, and so describing her work as “delicate” becomes all too loaded with the gendered expectations laden in that word.

Yes, it could be lazy to describe these paintings as delicate, too often shorthand for “feminine.” But it’s true—her work here is delicate in a “feminine way,” insofar as feminine expresses the hard work without commensurate accolades. Anyone who’s spent time painting knows that delicate touch is built of facility as much as out of care. Delicacy is tactile, in the way that demands a heightening of the senses, demanding increased awareness. It is perhaps not a mistake that as a noun, delicacy connotes a refined sensory experience. Delicate touch is practiced and expert.

Guerrero relies on this refined, delicate touch to conjure difficult images—not for their immensely crafted details or their photographic-realism. Rather, she draws inspiration from the first marks of rain to wet the pavement, highlighting a streak of grease. These things are unintentional, unfinished and undefined. It’s challenging to recreate the unintentional and accidental. Great painting, despite all the rumors, is not borne of accident. Yes, chance is involved, but honest painters will admit that we must create moments of chance. We select tools and methods to create imperfections, for their desired level of loss of control, and once those accidents appear, we may edit and fuss and become particular.

Guerrero uses these decisions to guide us through washes, opaque streaks, and diffused edges, all mixed in among what appear to be larger hurried brush-strokes, indicating bursts of movement. Some marks are the result of true accidents, some meticulously manufactured—in this tension, for all the solemnity of this body of work, there is a shimmering humor. The work of To Sink, Revisited plies in static, unrecognition, misrecognition, noise, and texture. You have to see it, or strain to see it, with your own eyes in order to appreciate the precision with which Guerrero has captured the fog that surrounds each of us.

— EM

To Sink, Revisited. 2019

86 pages. Edition of 175.

Essay: Emmanuel Mauleón

Translation to Spanish: Ana Larrea

Photography and Design: Blanca Guerrero